Impact of Autism and Coping Strategies in Indian-American Families.

Hari Srinivasan

APA Poster

Abstract

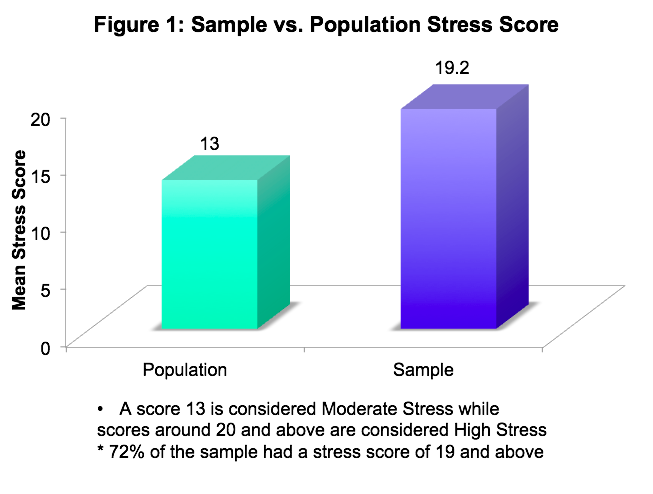

This paper explores the impact of autism and coping strategies amongst Indian-American families living in the San Francisco Bay Area. Descriptive information on the challenges faced, coping strategies and a stress score (as measured by the Cohen Perceived Stress Scale) was gathered from 18 Indian-American parents of individuals with autism. The study finds that high levels of stress amongst the ASD families (sample mean of 19.2) compared to the non-ASD families (population mean of 13). The study found that the age of the ASD family member does not seem to influence stress levels. There is however a direct correlation between the severity of challenging ASD symptoms and the level of stress.

This study suggests that if causes are better understood about the underlying physiological conditions for each specific case of autism, rather than classifying autism into one broad bucket, it may lead to more targeted treatments and better support systems could be put in place as well.

Positive outcomes for ASD individuals lead to less stress for families. Families also need more comprehensive support and resources in planning and supporting the needs of their ASD family member. Less stress for families leads to better outcomes for the ASD individuals.

Introduction

- Severity of ASD is a range due to the combinations of symptoms such as communication skills, socio-emotional skills and behaviors.

- Externalizing/maladaptive behaviors are a huge contributor to severity e.g.: hyperactivity and focus issues, mood issues (resulting in meltdowns, anxiety issues), obsessive compulsive and repetitive behaviors, sleep disturbances and Sensory Dysregulation.

- Dealing with this challenges causes significant stress for families given that the physiological basis of autism is still largely unknown..

Previous Literature indicates

- Severity (externalizing behaviors) has correlated with increased stress across multiple studies.

- Stress impacted not only the parents health levels, but also their effectiveness in interventions for their ASD children. Parental Stress resulted in stress for the ASD individuals and siblings.

- Studies done in China and India indicate that cultural issues can affect stress and coping skills

Method

- Sample comprised 18 Parents of ASD Individuals of Indian-Asian Origin living in Bay Area.

- Stress was measured using the Cohen Perceived Stress Scale.

- An ASD Severity/Challenge Score was determined through a parental ranking of each of the following symptoms for each ASD individual. (Scale 1 – mild, 2- moderate, 3 severe. The scores were then added to obtain the ASD Challenge/Severity Score)

- Parental Perception of ASD person’s functional level

- Communication Skill Level

- Hyperactivity/Focus

- Temper Tantrums/ Mood Swings

- Self Stimulatory Behaviors

- Sleep Disturbance Issues

- Obsessive Compulsive Behaviors.

- ASD individuals classified into ages 0-10, 11-17 and 18+ yrs.

- Families were interviewed to make qualitative observations on their stress and coping.

- Informed Consent and Demographic Profile was obtained

Results

Results agreed with Stated Hypothesis.

- Families of ASD individuals will tend to experience high levels of stress.

- There will not be a correlation between age of the ASD individual and level of stress for families

- There will be a direct correlation between severity of ASD symptoms and stress for the families.

Discussion

Stressors for families

- Significant social isolation. Limited to places their ASD family member can tolerate, dietary restrictions, unpredictability of child’s public behavior, intolerance/questioning of strangers

- Maze of therapies, medical treatments, insurance, legal paperwork. Lot of guesswork as to what the child needs or what to try next.

- ASD individual may need lifelong support and 24/7 care. Constant need for advocacy in education, medical and with public/private agencies

- One parent quits or works a less paid job for flexible hours. Those who went back to work felt guilty about time away. Those who did not regret loss of income.

- Steep cost of therapies/treatment/staff, possibly lifelong

- Siblings resentful over less parental time or become surrogate parents. Parental guilt about loss of the sibling’s childhood

- Worry over long term care and quality of life of ASD individual. Aging parents may not be able to help their ASD adult.

- Lifelong guilt of “what ifs,” and not having done enough.

- Bouts of sadness and depression

Coping Strategies

- Easier to focus on solving small issues than think on the “overwhelmingly scary,” Autism

- Keep pushing for improvements at each stage to improve quality of life for disabled family member. Start planning for long term housing and other needs for their child.

- Major source of emotional support was through parental support groups who formed the main basis of their social network.

- In some, lack of extended family pushed them towards problem solving approach as there was “no one else to pick up pieces.”

Cultural Factors

- Most families claimed zero correlation between ethnicity and coping strategies.

- Interview responses however revealed that some engaged in behaviors noticed in the Chinese and Indian studies such as hiding the diagnosis from family members.

Health Risks for Stressed Parents as they age.

Conclusion

- Autism significantly adds to stress levels for families. Stress is also directly correlated to the severity of ASD Symptoms, especially the presence of externalizing behaviors.

- Increased stress will lead to less positive for families and for the affected ASD individual.

Suggestions

- Rather than classify all the permutations and combinations of observable behavior into one broad bucket called Autism Spectrum, more investigation is required into its underlying physiological biochemical issues.

- Families require more comprehensive assistance and support rather than the piecemeal approach from various agencies to help navigate the unchartered waters of Autism

- These will lead to

- Targeted Treatments/ Therapies

- Lower Stress for Families

- Better outcomes for ASD individuals

FULL PAPER BELOW

Impact of Autism and Coping Strategies in Indian-American Families

Hari Srinivasan

FULL PAPER BELOW

Impact of Autism and Coping Strategies in Indian-American Families

Hari Srinivasan

Abstract

This paper explores the impact of autism and coping strategies amongst Indian-American families living in the San Francisco Bay Area. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a lifelong neurological disorder with its onset in early childhood. Descriptive information on the challenges, coping strategies and stress (as measured by the Cohen Perceived Stress Scale) was gathered from 18 Indian-American parents of individuals with autism. The study finds high levels of stress amongst the ASD families (sample mean of 19.2) compared to the population mean of 13. The study found that the age of the ASD family member does not seem to influence stress levels for the family. There is however a direct correlation between the severity of challenging ASD symptoms and the level of stress. Increased stress levels will lead to less positive outcomes for the caregivers such as impacting their physical and mental health. In addition, it will reduce the capacity of the caregiver to manage the challenges of Autism leading to less positive outcomes for the ASD individual.

This study suggests that if causes are better understood about the underlying physiological conditions for each specific case of autism, rather than classifying autism into one broad bucket, it may lead to more targeted treatments. Positive outcomes for ASD individuals lead to less stress for their families. Families also need more comprehensive support and resources in planning and supporting the needs of their ASD family member. Less stress for families leads to better outcomes for ASD family members.

Keywords: Autism, Autism Spectrum Disorder, ASD, Perceived Stress Scale, DSM-V, ADHD, OCD

This paper explores the impact of autism and coping strategies amongst Indian-American families living in the San Francisco Bay Area. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a lifelong neurological disorder with its onset in early childhood. Descriptive information on the challenges, coping strategies and stress (as measured by the Cohen Perceived Stress Scale) was gathered from 18 Indian-American parents of individuals with autism. The study finds high levels of stress amongst the ASD families (sample mean of 19.2) compared to the population mean of 13. The study found that the age of the ASD family member does not seem to influence stress levels for the family. There is however a direct correlation between the severity of challenging ASD symptoms and the level of stress. Increased stress levels will lead to less positive outcomes for the caregivers such as impacting their physical and mental health. In addition, it will reduce the capacity of the caregiver to manage the challenges of Autism leading to less positive outcomes for the ASD individual.

This study suggests that if causes are better understood about the underlying physiological conditions for each specific case of autism, rather than classifying autism into one broad bucket, it may lead to more targeted treatments. Positive outcomes for ASD individuals lead to less stress for their families. Families also need more comprehensive support and resources in planning and supporting the needs of their ASD family member. Less stress for families leads to better outcomes for ASD family members.

Keywords: Autism, Autism Spectrum Disorder, ASD, Perceived Stress Scale, DSM-V, ADHD, OCD

Impact of Autism and Coping Strategies in Indian-American Families

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurological disorder with an onset during early infancy and childhood. The DSM-V classification of ASD continues to be based on observations of external behaviors which focus on deficits in social-emotional skills, repetitive behaviors, and communication skills. Add to this a whole host of co-morbid conditions such as Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder (ADHD), Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD), mood disorders (eg: Bipolar Disorder), sleep disorders and Sensory Dysregulation, which can contribute to additional challenging or maladaptive externalizing behaviors. Epigenetics could also play a role wherein the environment affects gene expression. A mix and match of varying degrees of severity in these parameters result in huge numbers of people that fit this spectrum disorder. The severity ranges from individuals who are nonverbal with or without a range of challenging behaviors to those who are barely distinguishable from their peers. One in every 68 children is being diagnosed with ASD in the United States today (NIMH).

This study focuses on families of Indian Origin in the San Francisco Bay Area, California. Cultural isolation is not a new phenomenon amongst immigrant families but its effect is compounded when faced with the additional challenges of a family member with a perplexing disability like Autism. It is to be expected that cultural factors could add another layer of complexity to the challenges for the many Indian-American families.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurological disorder with an onset during early infancy and childhood. The DSM-V classification of ASD continues to be based on observations of external behaviors which focus on deficits in social-emotional skills, repetitive behaviors, and communication skills. Add to this a whole host of co-morbid conditions such as Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder (ADHD), Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD), mood disorders (eg: Bipolar Disorder), sleep disorders and Sensory Dysregulation, which can contribute to additional challenging or maladaptive externalizing behaviors. Epigenetics could also play a role wherein the environment affects gene expression. A mix and match of varying degrees of severity in these parameters result in huge numbers of people that fit this spectrum disorder. The severity ranges from individuals who are nonverbal with or without a range of challenging behaviors to those who are barely distinguishable from their peers. One in every 68 children is being diagnosed with ASD in the United States today (NIMH).

This study focuses on families of Indian Origin in the San Francisco Bay Area, California. Cultural isolation is not a new phenomenon amongst immigrant families but its effect is compounded when faced with the additional challenges of a family member with a perplexing disability like Autism. It is to be expected that cultural factors could add another layer of complexity to the challenges for the many Indian-American families.

Stress and Coping in Theory

Theories on stress and coping have in large part been influenced by landmark works of psychologists like Richard S. Lazarus (1922-2002) and Susan Folkman. Their Transactional Model of Stress and Coping has the viewpoint of a person-environment transaction. It defines stress as, “demands that exceed the personal and social resources the individual is able to mobilize." (Lazarus, 2003). Stress therefore, is the sum of the threat posed by the stressor and the cognitive assessment of available resources to mitigate the stress. In the model, a primary cognitive appraisal leads to three sorts of judgements regarding the stressor, which in turn determines their coping mechanism. When the stressor is viewed as a challenge it will elicit a positive response. When the stressor presents a threat it implies future harm, while a harm-loss stressor implies the damage has already been done (Lazarus, 2003). The autism diagnosis, which is often presented as a fait-accompli to parents and family, would put it firmly in the category of a harm-loss stressor as well as a threat to the future life of the affected family member. In fact, primary appraisals may not even take place when a person is thrown into a stressful situation such as learning about and dealing with the lifelong diagnosis of a family member. Secondary appraisals which can occur simultaneously with primary appraisals deal with the emotions and coping mechanisms (both positive and negative) in dealing with the stress. The model however provides hope in that stress is viewed as within the control of the individual, which implies that coping techniques can be taught or modified to lessen the effects of stress.

A model that has been used as a measure of family adaptation as part of the coping process is the ABCX, developed by Cavan and Ranck in 1938. At a high level the interaction in this model are, “stressors (A), resources (B), appraisals (C), coping (BC) and adaptation(X).” (McStay et al, 2014). The autism diagnosis and maladaptive behavior would clearly be the stressors in this model. Blackledge and Hay3es (2006) advocate the Acceptance and Commitment Theory as an effective coping tool with its primary focus on “positively reframing the traumatic and stressful event.”

Theories on stress and coping have in large part been influenced by landmark works of psychologists like Richard S. Lazarus (1922-2002) and Susan Folkman. Their Transactional Model of Stress and Coping has the viewpoint of a person-environment transaction. It defines stress as, “demands that exceed the personal and social resources the individual is able to mobilize." (Lazarus, 2003). Stress therefore, is the sum of the threat posed by the stressor and the cognitive assessment of available resources to mitigate the stress. In the model, a primary cognitive appraisal leads to three sorts of judgements regarding the stressor, which in turn determines their coping mechanism. When the stressor is viewed as a challenge it will elicit a positive response. When the stressor presents a threat it implies future harm, while a harm-loss stressor implies the damage has already been done (Lazarus, 2003). The autism diagnosis, which is often presented as a fait-accompli to parents and family, would put it firmly in the category of a harm-loss stressor as well as a threat to the future life of the affected family member. In fact, primary appraisals may not even take place when a person is thrown into a stressful situation such as learning about and dealing with the lifelong diagnosis of a family member. Secondary appraisals which can occur simultaneously with primary appraisals deal with the emotions and coping mechanisms (both positive and negative) in dealing with the stress. The model however provides hope in that stress is viewed as within the control of the individual, which implies that coping techniques can be taught or modified to lessen the effects of stress.

A model that has been used as a measure of family adaptation as part of the coping process is the ABCX, developed by Cavan and Ranck in 1938. At a high level the interaction in this model are, “stressors (A), resources (B), appraisals (C), coping (BC) and adaptation(X).” (McStay et al, 2014). The autism diagnosis and maladaptive behavior would clearly be the stressors in this model. Blackledge and Hay3es (2006) advocate the Acceptance and Commitment Theory as an effective coping tool with its primary focus on “positively reframing the traumatic and stressful event.”

Literature Review

Increasing awareness of the stress placed on families of individuals with Autism, has led to a huge body of literature in this area in recent years. Studies have primarily focused on either, “the severity of autism, child externalizing behaviors, or social support,” as the independent variable(s), (Falk et al. 2014). Falk et al. examined, “factors predicting stress, anxiety and depression,” in 479 parents of children with autism, ages 0-17. Parental support systems were found to play a bigger role than child variables. Falk et al. also point to a study by Moore (2009) which showed parents as adhering more to medical recommendations for their child than behavioral recommendations. Moore explained this disparity by pointing to the, “emotional challenge inherent in following through with behavioral management programs for children with autism.”. Moore goes on to add that, “the elevated levels of mental health problems experienced by this parental group may reduce their capacity to manage such challenges, thus negatively impacting their ability to implement programs of arguable benefit to their child(ren) with Autism.”

An investigative study by Seymour et al. (2013) on the, “relationship between the [ASD] child’s problematic behaviors and maternal coping and fatigue,” concluded that behavioral challenges led to a cycle of parental stress and ineffective coping strategies. McStay et al. (2014), investigated, “potential predictors of [parental] stress and family quality of life,” in 196 Australian families of children with Autism, ages 3-16 years. McStay’s study made use of the ABCX Formula explained earlier. Findings corroborated, “the negative impact of child externalizing behaviors and highlight the importance of family sense of coherence on positive parental outcomes.” McStay et al. allude to Patterson’s study (1988), which highlights, “positive outcomes and resilience through ... family adaptation, the process of restructuring family characteristics to adjust to the impact of major life stressors and strains.”

Miranda et al. (2015) undertook a comparative study of stress levels in the parental populations of ASD, ADHD, ASD along with ADHD, and a Control group. The measure of stress used was the PSI scale which is generally used for parents of children under 12. Not surprisingly, their general conclusion was that disability produced more stress vs. no disability. Co-morbidity also presented more stress than a single diagnosis. An earlier study by Steijn et al. (2013) on 174 families with ASD (with or without additional ADHD) had arrived at similar findings. In fact, Steijn et al. go onto speculate that stress and depression in the parent(s) could lead to stress and depression for both their ASD and non-ASD children. One can easily extrapolate these findings to other co-morbid conditions with maladaptive and externalizing behaviors such as OCD, Bipolar Disorder, Sleep Disorders and Sensory Dysregulation (that can cause self-stimulatory behaviors). Ergo, the presence of these comorbid conditions in addition to the ASD diagnosis would present an additional level of stress.

Hastings et al. (2005) identified four predominant coping strategies amongst the parental population of children with autism:

(1) Active-avoidance coping (substance abuse, self-blame, venting emotions); (2) Problem-focused coping (planning, taking action to address problem, seeking social support); (3) Positive coping (humor, positive reframing, acceptance and emotional social support to cope); and (4) Religious / denial coping (drawing on spirituality or pretending the problem does not exist). (Hastings et al. 2005)

Clearly, the reactive coping strategies span both positive and negative outcomes.

Cultural factors could also influence outcomes as examined in the study of 368 Chinese Families by Wang et al. (2011). According to the study, the one-child policy of China made it all the more difficult for Chinese families to accept an autism diagnosis. There was also “social-stigma and shame,” associated with the diagnosis which reduced “help-seeking” behaviors. Wang et al, point to a study by Shek and Tsang (1993) where avoidance was the most common coping strategy as families strove to hide the diagnosis especially at an early age from family and friends and engaged in more emotion-focused coping strategies (vs problem focused or relationship-focused). Parents also tended to use “internal coping strategies such as forbear,” rather than reaching out for support. Similar findings are also reflected in the coping strategies amongst parents of children with autism in India (Breziz et al. 2015).

Cultural differences have been mentioned in this literature review as this study attempts to look at the stresses of Autism on families of Asian-Indian origin living in the United States. The current study also attempts to look at any correlational trends between the age of the ASD individual and the stress experienced by family members. That is, as the child with ASD ages, does the stress level improve or degrade.

Key points from the literature review thus indicate

- Severity (externalizing behaviors) has correlated with increased stress across multiple studies. Comorbid conditions, especially those with, “acting out behaviors” (eg: ADHD) compounded the level of stress

- Stress impacted not only the parents health levels, but also their effectiveness in interventions for their ASD children. Parental Stress resulted in stress for the ASD individuals and siblings.

- Cultural issues affect stress and coping skills as shown in studies done in China and India.

Hypothesis

Increasing awareness of the stress placed on families of individuals with Autism, has led to a huge body of literature in this area in recent years. Studies have primarily focused on either, “the severity of autism, child externalizing behaviors, or social support,” as the independent variable(s), (Falk et al. 2014). Falk et al. examined, “factors predicting stress, anxiety and depression,” in 479 parents of children with autism, ages 0-17. Parental support systems were found to play a bigger role than child variables. Falk et al. also point to a study by Moore (2009) which showed parents as adhering more to medical recommendations for their child than behavioral recommendations. Moore explained this disparity by pointing to the, “emotional challenge inherent in following through with behavioral management programs for children with autism.”. Moore goes on to add that, “the elevated levels of mental health problems experienced by this parental group may reduce their capacity to manage such challenges, thus negatively impacting their ability to implement programs of arguable benefit to their child(ren) with Autism.”

An investigative study by Seymour et al. (2013) on the, “relationship between the [ASD] child’s problematic behaviors and maternal coping and fatigue,” concluded that behavioral challenges led to a cycle of parental stress and ineffective coping strategies. McStay et al. (2014), investigated, “potential predictors of [parental] stress and family quality of life,” in 196 Australian families of children with Autism, ages 3-16 years. McStay’s study made use of the ABCX Formula explained earlier. Findings corroborated, “the negative impact of child externalizing behaviors and highlight the importance of family sense of coherence on positive parental outcomes.” McStay et al. allude to Patterson’s study (1988), which highlights, “positive outcomes and resilience through ... family adaptation, the process of restructuring family characteristics to adjust to the impact of major life stressors and strains.”

Miranda et al. (2015) undertook a comparative study of stress levels in the parental populations of ASD, ADHD, ASD along with ADHD, and a Control group. The measure of stress used was the PSI scale which is generally used for parents of children under 12. Not surprisingly, their general conclusion was that disability produced more stress vs. no disability. Co-morbidity also presented more stress than a single diagnosis. An earlier study by Steijn et al. (2013) on 174 families with ASD (with or without additional ADHD) had arrived at similar findings. In fact, Steijn et al. go onto speculate that stress and depression in the parent(s) could lead to stress and depression for both their ASD and non-ASD children. One can easily extrapolate these findings to other co-morbid conditions with maladaptive and externalizing behaviors such as OCD, Bipolar Disorder, Sleep Disorders and Sensory Dysregulation (that can cause self-stimulatory behaviors). Ergo, the presence of these comorbid conditions in addition to the ASD diagnosis would present an additional level of stress.

Hastings et al. (2005) identified four predominant coping strategies amongst the parental population of children with autism:

(1) Active-avoidance coping (substance abuse, self-blame, venting emotions); (2) Problem-focused coping (planning, taking action to address problem, seeking social support); (3) Positive coping (humor, positive reframing, acceptance and emotional social support to cope); and (4) Religious / denial coping (drawing on spirituality or pretending the problem does not exist). (Hastings et al. 2005)

Clearly, the reactive coping strategies span both positive and negative outcomes.

Cultural factors could also influence outcomes as examined in the study of 368 Chinese Families by Wang et al. (2011). According to the study, the one-child policy of China made it all the more difficult for Chinese families to accept an autism diagnosis. There was also “social-stigma and shame,” associated with the diagnosis which reduced “help-seeking” behaviors. Wang et al, point to a study by Shek and Tsang (1993) where avoidance was the most common coping strategy as families strove to hide the diagnosis especially at an early age from family and friends and engaged in more emotion-focused coping strategies (vs problem focused or relationship-focused). Parents also tended to use “internal coping strategies such as forbear,” rather than reaching out for support. Similar findings are also reflected in the coping strategies amongst parents of children with autism in India (Breziz et al. 2015).

Cultural differences have been mentioned in this literature review as this study attempts to look at the stresses of Autism on families of Asian-Indian origin living in the United States. The current study also attempts to look at any correlational trends between the age of the ASD individual and the stress experienced by family members. That is, as the child with ASD ages, does the stress level improve or degrade.

Key points from the literature review thus indicate- Severity (externalizing behaviors) has correlated with increased stress across multiple studies. Comorbid conditions, especially those with, “acting out behaviors” (eg: ADHD) compounded the level of stress

- Stress impacted not only the parents health levels, but also their effectiveness in interventions for their ASD children. Parental Stress resulted in stress for the ASD individuals and siblings.

- Cultural issues affect stress and coping skills as shown in studies done in China and India.

H1: Families of Individuals with ASD will tend to experience high levels of stress.

H2: There will not be a correlation between age of ASD individual and level of stress for families.

H3: There will be a direct correlation between severity of Autism symptoms and stress for the families.

Method

Participants

Parents of individuals with Autism were recruited from members of the South Asian Parental Support group, Jeena, based in Milpitas, California. Participant parents were of Asian Indian Origin; either immigrants or first generation in the United States. Families were assigned to the following categories: Elementary School Age (upto age 9), Middle/High School (ages 10-17) and Adult (18 and above)

Parents of individuals with Autism were recruited from members of the South Asian Parental Support group, Jeena, based in Milpitas, California. Participant parents were of Asian Indian Origin; either immigrants or first generation in the United States. Families were assigned to the following categories: Elementary School Age (upto age 9), Middle/High School (ages 10-17) and Adult (18 and above)

Testing Materials and Procedure

PSS Questionnaire: The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) was used as a measure of stress for this study (Appendix B). The PSS was chosen as it is very short, easy to administer and also freely downloadable. The PSS is a well acknowledged, peer-reviewed scale and has been widely used since its development in 1988. According to it’s author, Stephen Cohen:

The PSS is a measure of the degree to which situations in one’s life are appraised as stressful. Items were designed to assess how unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overloaded respondents find their lives to be. The scale also includes a number of direct queries about current levels of experienced stress. Moreover, the questions are of a general nature and hence are relatively free of content specific to any sub-population group. The questions in the PSS ask about feelings and thoughts during the last month. In each case, respondents are asked how often they felt a certain way. (Cohen, 1983)

The questions on the PSS are scored on a scale of 0-4. (0 = Never, 1 = Almost Never, 2 = Sometimes, 3 = Fairly Often, 4 = Very Often.). The scoring scale for questions 4, 5, 8 and 9 are reversed as they indicate positive scores. The PSS has been normally distributed for the US population. Individual scores on the PSS range from 0-40 with 13 being considered moderate stress levels and scores around 20 and above indicating high levels of stress.

ASD Challenge Score (ASD Severity): Since communication ability, level of independence in daily living skills and maladaptive and externalizing behaviors often contribute significantly to the challenges of coping with autism for ASD individuals and their families, the following information was gathered about each ASD individual.

- Parental report of overall functioning level of the ASD family member. (1=Mild, 2=Medium, 3=severe)

- Communication Level (1=Verbal, 2=Moderately Verbal, 3=Non-Verbal)

- Independence in Daily Living Skills (1=Mostly Independent, 2 = Mixed Levels, 3 = Prompt Dependent or Needs Assistance for most)

- Externalizing Behaviors. A scale of 1= High, 2 = Medium, 3=Low for each listed below

- -- Hyperactivity/ Focus

- -- Temper Tantrums/ Mood Swings

- -- Self Stimulatory Behaviors (Repetitive motor/oral movements with the body/objects to serve some underlying function such as sensory seeking, attention, mitigate anxiety, avoiding demands, communicating etc.)

- -- Sleep Disturbance Issues (which in turn affect sleep patterns of caregivers)

- -- Obsessive Compulsive Behaviors

The scores on these factors were added to give an rough estimate of the challenge presented by the ASD symptoms for families, termed as the ASD Challenge score in this paper. Essentially, the ASD Challenge score is indicative of the ASD severity.

Semi-Structured Interview: Participants were asked questions in the form of a semi - structured interview (Appendix C) in order to make quantitative observations on their stress and coping.

PSS Questionnaire: The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) was used as a measure of stress for this study (Appendix B). The PSS was chosen as it is very short, easy to administer and also freely downloadable. The PSS is a well acknowledged, peer-reviewed scale and has been widely used since its development in 1988. According to it’s author, Stephen Cohen:

The PSS is a measure of the degree to which situations in one’s life are appraised as stressful. Items were designed to assess how unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overloaded respondents find their lives to be. The scale also includes a number of direct queries about current levels of experienced stress. Moreover, the questions are of a general nature and hence are relatively free of content specific to any sub-population group. The questions in the PSS ask about feelings and thoughts during the last month. In each case, respondents are asked how often they felt a certain way. (Cohen, 1983)

The questions on the PSS are scored on a scale of 0-4. (0 = Never, 1 = Almost Never, 2 = Sometimes, 3 = Fairly Often, 4 = Very Often.). The scoring scale for questions 4, 5, 8 and 9 are reversed as they indicate positive scores. The PSS has been normally distributed for the US population. Individual scores on the PSS range from 0-40 with 13 being considered moderate stress levels and scores around 20 and above indicating high levels of stress.

ASD Challenge Score (ASD Severity): Since communication ability, level of independence in daily living skills and maladaptive and externalizing behaviors often contribute significantly to the challenges of coping with autism for ASD individuals and their families, the following information was gathered about each ASD individual.

- Parental report of overall functioning level of the ASD family member. (1=Mild, 2=Medium, 3=severe)

- Communication Level (1=Verbal, 2=Moderately Verbal, 3=Non-Verbal)

- Independence in Daily Living Skills (1=Mostly Independent, 2 = Mixed Levels, 3 = Prompt Dependent or Needs Assistance for most)

- Externalizing Behaviors. A scale of 1= High, 2 = Medium, 3=Low for each listed below

- -- Hyperactivity/ Focus

- -- Temper Tantrums/ Mood Swings

- -- Self Stimulatory Behaviors (Repetitive motor/oral movements with the body/objects to serve some underlying function such as sensory seeking, attention, mitigate anxiety, avoiding demands, communicating etc.)

- -- Sleep Disturbance Issues (which in turn affect sleep patterns of caregivers)

- -- Obsessive Compulsive Behaviors

The scores on these factors were added to give an rough estimate of the challenge presented by the ASD symptoms for families, termed as the ASD Challenge score in this paper. Essentially, the ASD Challenge score is indicative of the ASD severity.

Semi-Structured Interview: Participants were asked questions in the form of a semi - structured interview (Appendix C) in order to make quantitative observations on their stress and coping.

Ethical Considerations

Informed Consent: The consent form (Appendix B) delineates the purpose of the study, the right to anonymity and the right to withdraw from the study.

Demographic Profile: A demographic profile (Appendix B) was obtained from all participants. As the investigator is an individual on the ASD spectrum with many of the challenges discussed in the study, the investigator’s family will not be a participant in the study.

Debriefing: At the conclusion of the study, participants will be debriefed about the results obtained from the study.

Informed Consent: The consent form (Appendix B) delineates the purpose of the study, the right to anonymity and the right to withdraw from the study.

Demographic Profile: A demographic profile (Appendix B) was obtained from all participants. As the investigator is an individual on the ASD spectrum with many of the challenges discussed in the study, the investigator’s family will not be a participant in the study.

Debriefing: At the conclusion of the study, participants will be debriefed about the results obtained from the study.

Results

A total of 18 parents participated in the study; 16 mothers and 2 fathers. Parental age ranged from 34-52 years. The ages of the ASD family member ranged from ages 6 to ages 23; 15 of them male, and 3 females.

Stress scores ranged from 13 to 27, along with an outlier stress score of 7 for one of the parents. The mean Stress Score was 19.2 and if the one outlier stress score of 7 is excluded, the sample mean stress score increases to 19.9. Approximately 72% of the sample scored 19 and above on the stress scale.

The stress scores were also plotted for the three different age groups as shown in Figure 2. There does not appear to be any huge difference across age groups. There were continuing or different challenges that contributed to high stress levels at each age level.

The stress scores were also plotted for the three different age groups as shown in Figure 2. There does not appear to be any huge difference across age groups. There were continuing or different challenges that contributed to high stress levels at each age level.

A total of 18 parents participated in the study; 16 mothers and 2 fathers. Parental age ranged from 34-52 years. The ages of the ASD family member ranged from ages 6 to ages 23; 15 of them male, and 3 females.

Stress scores ranged from 13 to 27, along with an outlier stress score of 7 for one of the parents. The mean Stress Score was 19.2 and if the one outlier stress score of 7 is excluded, the sample mean stress score increases to 19.9. Approximately 72% of the sample scored 19 and above on the stress scale.

The stress scores were also plotted for the three different age groups as shown in Figure 2. There does not appear to be any huge difference across age groups. There were continuing or different challenges that contributed to high stress levels at each age level.

Figure 3 shows the relationship between the ASD severity and the corresponding stress levels.

The semi-structured interview provided a deeper insight into the impact that coping with the challenges of ASD symptoms have on the family. These findings will be covered in the Discussion section that follows.

The semi-structured interview provided a deeper insight into the impact that coping with the challenges of ASD symptoms have on the family. These findings will be covered in the Discussion section that follows.

Figure 3 shows the relationship between the ASD severity and the corresponding stress levels.

The semi-structured interview provided a deeper insight into the impact that coping with the challenges of ASD symptoms have on the family. These findings will be covered in the Discussion section that follows.

Discussion

The data supports the first hypothesis in that families of individuals with Autism tend to experience high levels of stress. The mean sample stress score of 19.2 (Figure 1) is around the range considered high stress on the PSS Stress Scale, where the population mean of 13 is considered moderate stress. In fact, if the one outlier score is excluded, the sample mean stress score increases to 19.9. Two of the sample parents scored 27 on the stress scale, with approximately 72% with a score 19 or more.

The second hypothesis that there is no direct correlation between the age of ASD individual and level of stress for families is illustrated by Figure 2. Stress appears to be on the high level for the family, irrespective of age of the ASD family member. Responses from the semi structured interviews reveal that different challenges appear at different stages in the ASD family member’s life, contributing to a continual cycle of stress. Parents report that the elementary years, the teen years and the adult years all bring their own unique set of challenges. It is to be noted that while neuro-typical individuals go through these phases, in the case of autism, families and the ASD individuals are attempting to cross barely-navigated paths of the adult world of Autism.

The third hypothesis of a positive correlation between severity of Autism symptoms and stress for the families is illustrated by Figure 3. The maladaptive challenging behaviors looked at in this study included temper tantrums, self-stimulatory behaviors, sleep disturbances, hyperactivity/focus and obsessive compulsive behaviors and communication levels. For instance if a child cannot get their needs met by communication, they will develop ways that are dysfunctional to express their unhappiness and get attention. Many of these behaviors add to unpredictability in daily life and drain the mental and physical energy of the ASD individual and their families, thereby increasing their stress. Interview responses support the correlation of a direct correlation between severity of ASD symptoms and Stress. Parents find it difficult to reach out for help when they are moving from crisis to crisis (eg: tantrums). The nature and cause of challenging behaviors are not properly understood by those in authority, so parents worry about their child in public. It stands to reason that a majority of the growing numbers of children with autism will grow up to become adults with ASD. Challenging behaviors in older or bigger adults can be especially tough to handle and not well understood by authorities (eg: police). When there was improvement in the challenging behaviors of the ASD individual, the stress also decreased correspondingly. Stress continued to be high for parents whose children still faced significant challenges as they approached adulthood.

The interview responses revealed some of the complexities that contribute to high levels of stress for family members of ASD individuals. For instance, there is significant social isolation. Families were limited by the places their ASD family member could tolerate. Some parents reported that the dietary restrictions (such as the gluten free, casein free diet) tried in the early years of Autism, limited socialization as their child would be upset at not eating what other children were eating. Outings and vacations required extensive planning and organization along with the stress of coping with the unpredictability of their child’s reaction, anxiety levels and meltdowns in reaction to the vagaries of travel. There was also less bonding between the whole family and their extended family as the family was unable to go to many family events. Parents often have difficulty in explaining their ASD family member’s brand of autism to friends and family. Parents felt that friends and family, let alone strangers, did not understand the needs of the ASD individual and often “questioned” the activities of the family. In addition, some families with typical children have tended to limit or avoid interaction with families with ASD individuals out of sheer ignorance of the issues involved. The result was often unintentional isolation as families of ASD individuals often ended up limiting their social circle to other such families. Families of ASD individuals with neuro-typical siblings tended to fare somewhat better on the social front to accommodate the needs of their neuro-typical child(ren).

Interview responses revealed some aspects of the multifaceted and demanding role expected of the parent. They have to establish a mode of communication for the ASD individual; building these communication skills can be a lifelong process. The parent often has to guess at the child’s needs, when the child has limited communication skills. The child has to be taught to socialize, focus, practise impulse control and reduce anxiety at transitions. The parent has to manage therapies, (bio)medical and dietary interventions and recreational activities. They have to advocate and ensure appropriate school placements and environments. A few parents in the sample had resorted to homeschooling when faced with the lack of appropriate placements. A veritable maze of advocacy paperwork is required for public services, private services, medical insurance, legal and other issues throughout the life of the ASD individual. Invariably the parent ends up being the 24/7 caretaker, which is tiring. There is high support staff turnover as this is a stressful yet underpaid profession. Unlike neuro-typical children, many ASD individuals may need lifelong support and guidance from their family even after reaching adulthood.

The diagnosis places an increased financial burden on families, thus draining both energy and the pocket. All participants spoke of the steep cost of therapies, treatments and quality support staff, much of which is not covered by insurance or by state support. The demanding nature of Autism often makes a potential two income household into a one income household . All parents (male or female) in the sample had college degrees with a significant number having professional degrees in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Medicine). Invariably, one of the parents (usually the mother), either gave up work, worked part time, worked at less financially-desirable jobs, or postponed careers due to the demanding nature of the autism disability. The parent was unable to commit to the time, travel and social demands at work or the employer was not understanding of such needs. There was a good deal of guilt amongst parents who went back to work after a few years later (time taken away from therapies) and amongst parents who could not work (loss of potential income.)

Siblings too were affected by the presence of an ASD family member. Parents in the sample have reported both positive and negative outcomes for siblings. Some neuro-typical siblings have been very accepting of their disabled family member and formed strong bonds. Others however have been resentful of the time spent by the parent on their disabled sibling and moved away from them. Siblings have also in a sense, had their childhood cut short, as they were required to always be the more mature person in every interaction and cope with the challenges of their disabled sibling’s autism symptoms. However the interaction has also developed a greater empathy and appreciation for the important things of life in them. In essence, neuro-typical siblings seem to either be resentful (and guilty about feeling resentful) or end up acting as another surrogate parent for their ASD sibling.

It is of little surprise that families of ASD individuals experience high levels of stress as reiterated by the data in this study. The initial diagnosis had been very hard to accept for most parents, leaving in its wake a sort of lifelong guilt of “what ifs?” They felt guilty about not trying everything or not doing enough. Parents reported some level of sadness and depression when they viewed neuro-typical children enjoying and doing many of the things their own ASD child struggled with or would probably never do. Parents reported feeling drained and disappointed when their child had a bad day or was not making progress despite a lot of effort, time and expense. Worry about the future for their ASD child loomed large, as most ASD individuals will outlive their parents and aging parents are not as capable of assisting their adult ASD children.

Hastings et al. (2005) had identified four predominant coping strategies amongst the parental population of children with autism as outlined in the literature review section. All the parents in this sample fall into the second coping category (Problem Focused Coping) and third coping category (Positive Coping). Though some feelings of guilt and blame continued to persist at some level over the years, a majority had taken on a problem-solving approach. One parent remarked that it was easier to focus on solving little issues and take matters one day at a time rather than imagining the complete picture of Autism which was overwhelmingly scary. Ironically, the lack of extended family for some of the parents in the sample has forced them to be problem-focussed. As one parent observed, “There were days I’ve completely broken down and cried for hours. But the next day you have to get up and work for your child no matter what. There is no (extended) family to offer moral support. So it’s good and bad.” Some of the parents have set high goals and expectations and systematically worked towards mitigating challenging symptoms and enhancing strengths at each step. Others have looked towards long term housing and financial arrangements for their child. While the initial rush was to somehow “cure” their child, it evolved to a practical acceptance of the neuro-diversity of their child even if they did not make significant improvement over the years. But at every stage, a number of parents in the group, kept pushing for further improvement in different aspects of their child’s life in order to improve the future quality of life for their ASD child. All sought emotional support through parental support organizations and formed close bonds with other such families and most have pointed to this avenue as a major source of their emotional coping. It should also be pointed out that a few mothers have found going back to work, even if it was part time, has helped give them a break of sorts. None of the parents in the sample engaged in any form of Religious/ Denial Coping where they drew on religion to deny the problem existed.

When asked as a direct question, a majority of parents did not feel their ethnic background influenced their level of stress or their coping strategies, with only one parent in the sample voicing such an impact. However responses to other interview questions indicated three parents (out of a sample size of 18), had engaged in the coping pattern of hiding the autism diagnosis from their friends and relatives especially in the early years. This type of coping pattern was part of the findings in the studies done in China (Wang et al. 2011) and India (Breziz et al. 2015) mentioned in the literature review.

The data supports the first hypothesis in that families of individuals with Autism tend to experience high levels of stress. The mean sample stress score of 19.2 (Figure 1) is around the range considered high stress on the PSS Stress Scale, where the population mean of 13 is considered moderate stress. In fact, if the one outlier score is excluded, the sample mean stress score increases to 19.9. Two of the sample parents scored 27 on the stress scale, with approximately 72% with a score 19 or more.

The second hypothesis that there is no direct correlation between the age of ASD individual and level of stress for families is illustrated by Figure 2. Stress appears to be on the high level for the family, irrespective of age of the ASD family member. Responses from the semi structured interviews reveal that different challenges appear at different stages in the ASD family member’s life, contributing to a continual cycle of stress. Parents report that the elementary years, the teen years and the adult years all bring their own unique set of challenges. It is to be noted that while neuro-typical individuals go through these phases, in the case of autism, families and the ASD individuals are attempting to cross barely-navigated paths of the adult world of Autism.

The third hypothesis of a positive correlation between severity of Autism symptoms and stress for the families is illustrated by Figure 3. The maladaptive challenging behaviors looked at in this study included temper tantrums, self-stimulatory behaviors, sleep disturbances, hyperactivity/focus and obsessive compulsive behaviors and communication levels. For instance if a child cannot get their needs met by communication, they will develop ways that are dysfunctional to express their unhappiness and get attention. Many of these behaviors add to unpredictability in daily life and drain the mental and physical energy of the ASD individual and their families, thereby increasing their stress. Interview responses support the correlation of a direct correlation between severity of ASD symptoms and Stress. Parents find it difficult to reach out for help when they are moving from crisis to crisis (eg: tantrums). The nature and cause of challenging behaviors are not properly understood by those in authority, so parents worry about their child in public. It stands to reason that a majority of the growing numbers of children with autism will grow up to become adults with ASD. Challenging behaviors in older or bigger adults can be especially tough to handle and not well understood by authorities (eg: police). When there was improvement in the challenging behaviors of the ASD individual, the stress also decreased correspondingly. Stress continued to be high for parents whose children still faced significant challenges as they approached adulthood.

The interview responses revealed some of the complexities that contribute to high levels of stress for family members of ASD individuals. For instance, there is significant social isolation. Families were limited by the places their ASD family member could tolerate. Some parents reported that the dietary restrictions (such as the gluten free, casein free diet) tried in the early years of Autism, limited socialization as their child would be upset at not eating what other children were eating. Outings and vacations required extensive planning and organization along with the stress of coping with the unpredictability of their child’s reaction, anxiety levels and meltdowns in reaction to the vagaries of travel. There was also less bonding between the whole family and their extended family as the family was unable to go to many family events. Parents often have difficulty in explaining their ASD family member’s brand of autism to friends and family. Parents felt that friends and family, let alone strangers, did not understand the needs of the ASD individual and often “questioned” the activities of the family. In addition, some families with typical children have tended to limit or avoid interaction with families with ASD individuals out of sheer ignorance of the issues involved. The result was often unintentional isolation as families of ASD individuals often ended up limiting their social circle to other such families. Families of ASD individuals with neuro-typical siblings tended to fare somewhat better on the social front to accommodate the needs of their neuro-typical child(ren).

Interview responses revealed some aspects of the multifaceted and demanding role expected of the parent. They have to establish a mode of communication for the ASD individual; building these communication skills can be a lifelong process. The parent often has to guess at the child’s needs, when the child has limited communication skills. The child has to be taught to socialize, focus, practise impulse control and reduce anxiety at transitions. The parent has to manage therapies, (bio)medical and dietary interventions and recreational activities. They have to advocate and ensure appropriate school placements and environments. A few parents in the sample had resorted to homeschooling when faced with the lack of appropriate placements. A veritable maze of advocacy paperwork is required for public services, private services, medical insurance, legal and other issues throughout the life of the ASD individual. Invariably the parent ends up being the 24/7 caretaker, which is tiring. There is high support staff turnover as this is a stressful yet underpaid profession. Unlike neuro-typical children, many ASD individuals may need lifelong support and guidance from their family even after reaching adulthood.

The diagnosis places an increased financial burden on families, thus draining both energy and the pocket. All participants spoke of the steep cost of therapies, treatments and quality support staff, much of which is not covered by insurance or by state support. The demanding nature of Autism often makes a potential two income household into a one income household . All parents (male or female) in the sample had college degrees with a significant number having professional degrees in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Medicine). Invariably, one of the parents (usually the mother), either gave up work, worked part time, worked at less financially-desirable jobs, or postponed careers due to the demanding nature of the autism disability. The parent was unable to commit to the time, travel and social demands at work or the employer was not understanding of such needs. There was a good deal of guilt amongst parents who went back to work after a few years later (time taken away from therapies) and amongst parents who could not work (loss of potential income.)

Siblings too were affected by the presence of an ASD family member. Parents in the sample have reported both positive and negative outcomes for siblings. Some neuro-typical siblings have been very accepting of their disabled family member and formed strong bonds. Others however have been resentful of the time spent by the parent on their disabled sibling and moved away from them. Siblings have also in a sense, had their childhood cut short, as they were required to always be the more mature person in every interaction and cope with the challenges of their disabled sibling’s autism symptoms. However the interaction has also developed a greater empathy and appreciation for the important things of life in them. In essence, neuro-typical siblings seem to either be resentful (and guilty about feeling resentful) or end up acting as another surrogate parent for their ASD sibling.

It is of little surprise that families of ASD individuals experience high levels of stress as reiterated by the data in this study. The initial diagnosis had been very hard to accept for most parents, leaving in its wake a sort of lifelong guilt of “what ifs?” They felt guilty about not trying everything or not doing enough. Parents reported some level of sadness and depression when they viewed neuro-typical children enjoying and doing many of the things their own ASD child struggled with or would probably never do. Parents reported feeling drained and disappointed when their child had a bad day or was not making progress despite a lot of effort, time and expense. Worry about the future for their ASD child loomed large, as most ASD individuals will outlive their parents and aging parents are not as capable of assisting their adult ASD children.

Hastings et al. (2005) had identified four predominant coping strategies amongst the parental population of children with autism as outlined in the literature review section. All the parents in this sample fall into the second coping category (Problem Focused Coping) and third coping category (Positive Coping). Though some feelings of guilt and blame continued to persist at some level over the years, a majority had taken on a problem-solving approach. One parent remarked that it was easier to focus on solving little issues and take matters one day at a time rather than imagining the complete picture of Autism which was overwhelmingly scary. Ironically, the lack of extended family for some of the parents in the sample has forced them to be problem-focussed. As one parent observed, “There were days I’ve completely broken down and cried for hours. But the next day you have to get up and work for your child no matter what. There is no (extended) family to offer moral support. So it’s good and bad.” Some of the parents have set high goals and expectations and systematically worked towards mitigating challenging symptoms and enhancing strengths at each step. Others have looked towards long term housing and financial arrangements for their child. While the initial rush was to somehow “cure” their child, it evolved to a practical acceptance of the neuro-diversity of their child even if they did not make significant improvement over the years. But at every stage, a number of parents in the group, kept pushing for further improvement in different aspects of their child’s life in order to improve the future quality of life for their ASD child. All sought emotional support through parental support organizations and formed close bonds with other such families and most have pointed to this avenue as a major source of their emotional coping. It should also be pointed out that a few mothers have found going back to work, even if it was part time, has helped give them a break of sorts. None of the parents in the sample engaged in any form of Religious/ Denial Coping where they drew on religion to deny the problem existed.

When asked as a direct question, a majority of parents did not feel their ethnic background influenced their level of stress or their coping strategies, with only one parent in the sample voicing such an impact. However responses to other interview questions indicated three parents (out of a sample size of 18), had engaged in the coping pattern of hiding the autism diagnosis from their friends and relatives especially in the early years. This type of coping pattern was part of the findings in the studies done in China (Wang et al. 2011) and India (Breziz et al. 2015) mentioned in the literature review.

Conclusion

No matter the coping strategies employed, the burden of care, advocacy and support falls mainly on the immediate family, without a comprehensive support system in place. The high levels of stress experienced will negatively impact the mental and physical health of caregivers as high stress levels is often linked to issues such as high BP, high cholesterol, chest pain, muscle tension, cardiovascular disease, depression, anger, irritability, and suppressed immunity (NIMH). As mentioned in the literature review, Moore (2009) had pointed out that stresses on the mental and physical health of parents will, “reduce their capacity to manage the challenges [of Autism] and their effectiveness in implementing,” the required measures needed for their ASD child. In essence, the negative impact on families will in turn impact outcomes for the ASD individuals.

Outside support for the family is often piecemeal, with public/ private/ medical services each focusing on very specific aspects of the disability. This creates a huge challenge as families attempt to coordinate and piece together a jigsaw puzzle of treatments, therapies and services in addition to coping with the daily challenges of a still largely unknown disorder and an uncertain future for the disabled member of their family. Currently there is no one stop solution for the varying permutations and combinations of symptoms that ASD has. Any medical breakthrough may benefit a specific subgroup that fits a certain underlying physiological biochemical profile. Families like to see results in their child from the treatments and therapies tried to keep themselves motivated to continue to work on positive outcomes.

This study suggests that if causes are better understood about the underlying physiological conditions for each specific case of autism, rather than classifying autism into one broad bucket, it may lead to more targeted treatments. Positive outcomes for ASD individuals lead to less stress for their families. Families also need more comprehensive support and resources in planning and supporting the needs of their ASD family member. Less stress for families leads to better outcomes for ASD family members.

References

Autism Speaks. (2016). Glossary of Terms. Retrieved October 25, 2016.

Blackledge, J.T., & Hayes, S., (2006) Using acceptance and commitment training in the support of parents of children with diagnosed with autism. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 28(1), 1-18

Brezis, R., Weisner, T., Daley, T., Singhal, N., Barua, M., & Chollera, S. (2015). Parenting a Child with Autism in India: Narratives Before and After a Parent-Child Intervention Program. Culture, Medicine & Psychiatry, 39(2), 277-298.

Cohen, S; Kamarck T; Mermelstein R (December 1983). "A global measure of perceived stress". Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 24(4): 385–396. doi:10.2307/2136404. PMID 6668417.

Cohen, S., & Williamson, G. (1988). Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In S. Spacapan & S. Oskamp (Eds.), The social psychology of health: Claremont Symposium on applied social psychology. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Falk, N., Norris, K., & Quinn, M. (2014). The Factors Predicting Stress, Anxiety and Depression in the Parents of Children with Autism.Journal Of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 44(12), 3185-3203.

Hastings, R., Kovshoff, H., Brown, T., Ward, N., Espinosa, F., & Remington, B. (2005). Coping strategies in mothers and fathers of pre-school and school age children with autism. Autism, 9(4), 377-391

Lazarus, R. S. (2003). AUTHOR'S RESPONSE: The Lazarus Manifesto for Positive Psychology and Psychology in General.Psychological Inquiry, 14(2), 173.

McStay, R., Trembath, D., & Dissanayake, C. (2014). Stress and Family Quality of Life in Parents of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Parent Gender and the Double ABCX Model.Journal Of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 44(12), 3101-3118.

Miranda, A., Tárraga, R., Fernández, M. I., Colomer, C., & Pastor, G. (2015). Parenting Stress in Families of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and ADHD. Exceptional Children, 82(1), 81-95.

NIMH » Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). (n.d.). Retrieved September 23, 2016, from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/prevalence/autism-spectrum-disorder-asd.shtml

Seymour, Monique, et al. "Fatigue, Stress And Coping In Mothers Of Children With An Autism Spectrum Disorder." Journal Of Autism & Developmental Disorders 43.7 (2013): 1547-1554. Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection. Web. 19 Sept. 2016.

Steijn, D., Oerlemans, A., Aken, M., Buitelaar, J., & Rommelse, N. (2014). The Reciprocal Relationship of ASD, ADHD, Depressive Symptoms and Stress in Parents of Children with ASD and/or ADHD.Journal Of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 44(5), 1064-1076.

Wang, P., Michaels, C. A., & Day, M. S. (2011). Stresses and Coping Strategies of Chinese Families with Children with Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. Journal Of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 41(6), 783-795.

No matter the coping strategies employed, the burden of care, advocacy and support falls mainly on the immediate family, without a comprehensive support system in place. The high levels of stress experienced will negatively impact the mental and physical health of caregivers as high stress levels is often linked to issues such as high BP, high cholesterol, chest pain, muscle tension, cardiovascular disease, depression, anger, irritability, and suppressed immunity (NIMH). As mentioned in the literature review, Moore (2009) had pointed out that stresses on the mental and physical health of parents will, “reduce their capacity to manage the challenges [of Autism] and their effectiveness in implementing,” the required measures needed for their ASD child. In essence, the negative impact on families will in turn impact outcomes for the ASD individuals.

Outside support for the family is often piecemeal, with public/ private/ medical services each focusing on very specific aspects of the disability. This creates a huge challenge as families attempt to coordinate and piece together a jigsaw puzzle of treatments, therapies and services in addition to coping with the daily challenges of a still largely unknown disorder and an uncertain future for the disabled member of their family. Currently there is no one stop solution for the varying permutations and combinations of symptoms that ASD has. Any medical breakthrough may benefit a specific subgroup that fits a certain underlying physiological biochemical profile. Families like to see results in their child from the treatments and therapies tried to keep themselves motivated to continue to work on positive outcomes.

This study suggests that if causes are better understood about the underlying physiological conditions for each specific case of autism, rather than classifying autism into one broad bucket, it may lead to more targeted treatments. Positive outcomes for ASD individuals lead to less stress for their families. Families also need more comprehensive support and resources in planning and supporting the needs of their ASD family member. Less stress for families leads to better outcomes for ASD family members.

References

Autism Speaks. (2016). Glossary of Terms. Retrieved October 25, 2016.

Blackledge, J.T., & Hayes, S., (2006) Using acceptance and commitment training in the support of parents of children with diagnosed with autism. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 28(1), 1-18

Brezis, R., Weisner, T., Daley, T., Singhal, N., Barua, M., & Chollera, S. (2015). Parenting a Child with Autism in India: Narratives Before and After a Parent-Child Intervention Program. Culture, Medicine & Psychiatry, 39(2), 277-298.

Cohen, S; Kamarck T; Mermelstein R (December 1983). "A global measure of perceived stress". Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 24(4): 385–396. doi:10.2307/2136404. PMID 6668417.

Cohen, S., & Williamson, G. (1988). Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In S. Spacapan & S. Oskamp (Eds.), The social psychology of health: Claremont Symposium on applied social psychology. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Falk, N., Norris, K., & Quinn, M. (2014). The Factors Predicting Stress, Anxiety and Depression in the Parents of Children with Autism.Journal Of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 44(12), 3185-3203.

Hastings, R., Kovshoff, H., Brown, T., Ward, N., Espinosa, F., & Remington, B. (2005). Coping strategies in mothers and fathers of pre-school and school age children with autism. Autism, 9(4), 377-391

Lazarus, R. S. (2003). AUTHOR'S RESPONSE: The Lazarus Manifesto for Positive Psychology and Psychology in General.Psychological Inquiry, 14(2), 173.

McStay, R., Trembath, D., & Dissanayake, C. (2014). Stress and Family Quality of Life in Parents of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Parent Gender and the Double ABCX Model.Journal Of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 44(12), 3101-3118.

Miranda, A., Tárraga, R., Fernández, M. I., Colomer, C., & Pastor, G. (2015). Parenting Stress in Families of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and ADHD. Exceptional Children, 82(1), 81-95.

NIMH » Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). (n.d.). Retrieved September 23, 2016, from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/prevalence/autism-spectrum-disorder-asd.shtml

Seymour, Monique, et al. "Fatigue, Stress And Coping In Mothers Of Children With An Autism Spectrum Disorder." Journal Of Autism & Developmental Disorders 43.7 (2013): 1547-1554. Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection. Web. 19 Sept. 2016.

Steijn, D., Oerlemans, A., Aken, M., Buitelaar, J., & Rommelse, N. (2014). The Reciprocal Relationship of ASD, ADHD, Depressive Symptoms and Stress in Parents of Children with ASD and/or ADHD.Journal Of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 44(5), 1064-1076.

Wang, P., Michaels, C. A., & Day, M. S. (2011). Stresses and Coping Strategies of Chinese Families with Children with Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. Journal Of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 41(6), 783-795.

Appendix A - Research Consent Form

Study Title: Impact of Autism on Families of Indian Origin

Principal Investigator: Hari Srinivasan, San Jose, City College

Description: You are invited to participate in a research study on the Impact of Autism on families of Indian origin living in the Bay Area. This study is being conducted as part of The Research Methods in Psychology course at San Jose City College.

You will be asked to fill the following items

-

A short survey

-

A Demographics Form

-

A few questions in the form of a semi-structured interview about your family and the ASD family member. As this student researcher has nonverbal autism, the questions will be emailed to you. Please provide as much detail as you can. A helper can record oral responses if that is your preference.

-

You may be asked a few follow up questions via email based on your response.

Time Commitment: Your participation should take no more than one hour.

Participants Rights: You have the right to withdraw your consent or discontinue participation at any time.

Confidentiality: Your name or the name of your ASD family member will not be used in any written materials resulting from this study unless you give the right to do so.

Contact Information: If you have any questions or concerns, you may contact the student researcher, Hari Srinivasan, at email4hari@gmail.com

SIGNATURE ________________________ Date __________________

Print Name of Participant: ______________________________________

Appendix B: Demographic Profile

Gender of Parent/Caregiver: Male / Female Age of Parent/Caregiver: _____

Profession: ____________ Age of ASD Family Member: __

Relationship to ASD Family Member:: Father / Mother / Sibling / Other

Does the ASD Family Member live with you in your home? (Yes/No):

PLEASE CHECK APPLICABLE BOXES FOR THE NEXT 5 ITEMS

-

Communication level of ASD Individual?

____ Very Verbal with Good Communication Skills

____ Moderately Verbal and Communication Skills

____ Non-Verbal

____ Uses Alternative Means of Communication

____ Other (Please elaborate):

2. Independence Level of ASD Individual (Check applicable box)

____ Independent for most if not all Daily Living Tasks

____ Mixed Levels depending on Task

____ Totally reliant on assistance and prompting

____ Other (Please elaborate)

3. Externalizing Behaviors exhibited by the ASD Individual. (Circle applicable )

High/Medium/Low: Hyperactivity and/or Focus Issues

High/Medium/Low: Temper Tantrums and Mood Swings

High/Medium/Low: Self-Stimulatory Behaviors

High/Medium/Low: Obsessive Compulsive / Repetitive Behaviors

High/Medium/Low: Sleep Issues

High/Medium/Low: Other (Please Elaborate):

4. Program the ASD individual is currently in:

____ Special Education / Post Secondary / Special Needs Adult Day Program

____ Home based Program / Home School

____ Mainstream Program (Elementary / Middle/High School, College)

5. Do you regard the ASD’s individual’s current symptoms as

____ Mild ____ Moderate ____ Severe

Study Title: Impact of Autism on Families of Indian Origin

Principal Investigator: Hari Srinivasan, San Jose, City College

Description: You are invited to participate in a research study on the Impact of Autism on families of Indian origin living in the Bay Area. This study is being conducted as part of The Research Methods in Psychology course at San Jose City College.

You will be asked to fill the following items

- A short survey

- A Demographics Form

- A few questions in the form of a semi-structured interview about your family and the ASD family member. As this student researcher has nonverbal autism, the questions will be emailed to you. Please provide as much detail as you can. A helper can record oral responses if that is your preference.

- You may be asked a few follow up questions via email based on your response.

Time Commitment: Your participation should take no more than one hour.

Participants Rights: You have the right to withdraw your consent or discontinue participation at any time.

Confidentiality: Your name or the name of your ASD family member will not be used in any written materials resulting from this study unless you give the right to do so.

Contact Information: If you have any questions or concerns, you may contact the student researcher, Hari Srinivasan, at email4hari@gmail.com

SIGNATURE ________________________ Date __________________

Print Name of Participant: ______________________________________

Appendix B: Demographic Profile

Gender of Parent/Caregiver: Male / Female Age of Parent/Caregiver: _____

Profession: ____________ Age of ASD Family Member: __

Relationship to ASD Family Member:: Father / Mother / Sibling / Other

Does the ASD Family Member live with you in your home? (Yes/No):

PLEASE CHECK APPLICABLE BOXES FOR THE NEXT 5 ITEMS

- Communication level of ASD Individual?

____ Very Verbal with Good Communication Skills

____ Moderately Verbal and Communication Skills

____ Non-Verbal

____ Uses Alternative Means of Communication

____ Other (Please elaborate):

2. Independence Level of ASD Individual (Check applicable box)

____ Independent for most if not all Daily Living Tasks

____ Mixed Levels depending on Task

____ Totally reliant on assistance and prompting

____ Other (Please elaborate)

3. Externalizing Behaviors exhibited by the ASD Individual. (Circle applicable )

High/Medium/Low: Hyperactivity and/or Focus Issues

High/Medium/Low: Temper Tantrums and Mood Swings

High/Medium/Low: Self-Stimulatory Behaviors

High/Medium/Low: Obsessive Compulsive / Repetitive Behaviors

High/Medium/Low: Sleep Issues

High/Medium/Low: Other (Please Elaborate):

4. Program the ASD individual is currently in:

____ Special Education / Post Secondary / Special Needs Adult Day Program

____ Home based Program / Home School

____ Mainstream Program (Elementary / Middle/High School, College)

5. Do you regard the ASD’s individual’s current symptoms as

____ Mild ____ Moderate ____ Severe

Appendix C: Semi-Structured Interview Questions

-

What has been the impact of Autism for your family in terms of:

a. Social Life

b. Work Front

c. Marriage Front

d. Financial Front

e. Medical Fron

f. Effect on Siblings

-

Do you think more severe symptoms or challenging behaviors increase familial stress.

-